Learning from the past

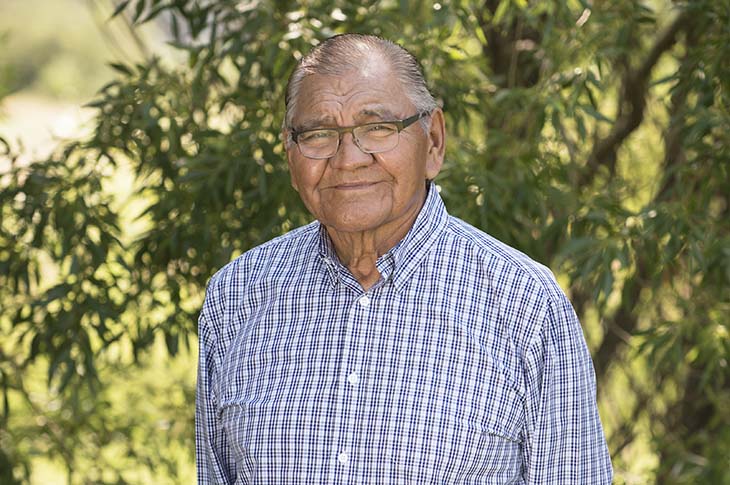

Riding with his parents in a rented horse-drawn buggy, seven-year-old Victor Buffalo couldn’t contain his excitement as they made the ten-mile journey to Ermineskin Indian Residential School.

Having fantasized with a friend about how great it would be, Buffalo couldn’t wait to see what his first day had in store.

It wasn’t until his parents went to leave without him that fear set in. Running after them, Buffalo was chased by two older boys and brought back to the school, crying and kicking.

“I don’t know when I stopped crying,” he says, reflecting back on that day.

A nun led Buffalo to the dormitory to bathe and change into new clothes. Instead of being called by his name, he was assigned a number.

The school was his home now. The year was 1948.

Life in residential school

For the next 14 years, Buffalo’s life was one of routine.

Every day began with early morning prayers before making the long trip to church on foot, regardless of the weather.

“I just remember the cold — the blowing snow as we walked two by two,” says Buffalo.

Catholic mass was nothing like the rituals he remembered from back home, and Buffalo longed for the familiarity of his people and culture.

“Before residential school, my family included me in traditional ceremonies with elders,” he says. “Those experiences always stayed in my heart and mind.” After mass, the children would return to school for breakfast, a quiet meal since no one was allowed to speak outside of a short 15-minute window. When Buffalo and his friends would speak, it was in English.

“We weren’t allowed to speak Cree because it was considered the language of the devil,” he says. “They called us savages.”

Buffalo sought escape in the pages of books and set his sights on finishing his education.

“Students were usually kicked out when they turned 16, but I kept coming back,” he says. “I was determined to graduate.”

In 1962, at the age of 20, he did just that.

Turning the page

Buffalo saw a brochure about SAIT and applied to the Industrial Chemical Technology program. He was accepted and made the three-hour journey to Calgary, driven by a parish priest.

The transition to his new life was overwhelming. He drew from his experience at residential school to get through it.

“I was determined to finish what I set out to do,” he said.

Spending most of his time on campus, studying and embracing the student experience, Buffalo graduated in 1964.

“I really enjoyed my time at SAIT,” he says.

Buffalo served as Chief of the Samson Creek Nation five times, developing educational and economic initiatives benefiting his people. He helped found Peace Hills Trust — Canada’s first Indigenous-owned financial institution — and established the Samson Education Trust Fund to expand educational opportunities for Indigenous youth.

He has received the Order of Canada, was inducted into the Alberta Business Hall of Fame and was named SAIT’s 2017 Distinguished Alumnus.

Orange Shirt Day

On Wednesday, Sept. 30, people across the country will wear orange to remember and honour an estimated 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children who attended residential schools in Canada.

🧡 Wear orange to honour residential school survivors, their families and communities on Wednesday, Sept. 30.

💡 Register to join more than 6,000 educators and 300,000 Canadian youth at the Every Child Matters: Reconciliation Through Education online event organized by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

📷 Take photos showcasing your orange shirt and share on social media using #EveryChildMatters, #OrangeShirtDay, #OSD and #hereatSAIT.

To learn more about SAIT’s commitment to Indigenous students, see the Indigenous Learner Success Strategy.

Oki, Âba wathtech, Danit'ada, Tawnshi, Hello.

SAIT is located on the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of Treaty 7 which includes the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina and the Îyârhe Nakoda of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney.

We are situated in an area the Blackfoot tribes traditionally called Moh’kinsstis, where the Bow River meets the Elbow River. We now call it the city of Calgary, which is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta.