Editor’s note: As LINK was going to press, the social enterprise featured in this story announced its closure, but research into alternative materials will continue in the Advanced Material Characterization (AMC) Lab mentioned below. “We look forward to exploring new opportunities with innovators in the ecosystem, using our expertise to support the development of novel composite materials and advance material science together," says Karla Rodriquez, AMC lab supervisor.

For North American takeout regulars, avoiding single-use plastics is no easy task when everything — including biodegradable plastic and paper containers — comes with environmental costs.

Earthware, an Alberta-based social enterprise, offers an alternative: a reusable takeout container program that enables restaurants to provide their customers with a sustainable, reusable takeout container. After rinsing, customers can drop the containers at any bottle depot for a refund. The containers are then collected by Earthware, sanitized and recirculated for reuse.

Now, the social enterprise is working with researchers at the Centre for Innovation and Research in Advanced Manufacturing and Materials (CIRAMM) — part of SAIT’s Applied Research and Innovation Services (ARIS) — on a multi-stage project to explore new container designs, optimized manufacturing processes, and sustainable materials that will hold up to frequent washes.

“The idea is to see if we can create a composite material for our containers that has less plastic and some natural fibres,” says John MacInnes, Earthware’s founder.

The CIRAMM team suggested testing a composite made from polypropylene and hemp hurd, a byproduct that’s typically thrown out after hemp is processed for textiles and other products.

“Hemp also grows very fast and doesn’t require much water,” says Karla Rodriguez, lab supervisor for CIRAMM’s Advanced Material Characterization (AMC) lab.

Hemp hurd contains substantial amounts of organic polymers, and testing showed that a hemp hurd/polypropylene blend is stronger than polypropylene alone — but there’s more work to be done.

“Currently, a recycling depot just has to melt down the plastic to produce a new material,” says Rodriguez. “We need to make sure the composite is recyclable, too.”

The research project also analyzed alternative manufacturing techniques. After testing vacuum forming, Earthware decided to stick with its current processes. “Injection molding is pretty fast, and it’s easier to manufacture locally,” says Rodriguez, adding that overseas manufacturing would increase the environmental impact.

Although hemp hurd holds potential, MacInnes is most excited to bring appealing new container designs to the market.

“The industry doesn’t really have any bespoke container designs,” he says. “Now we’ve got some great containers that we could make with plastic or a new material.”

We’ll just have to wait for the next phase in this collaborative research project to learn which material wins out.

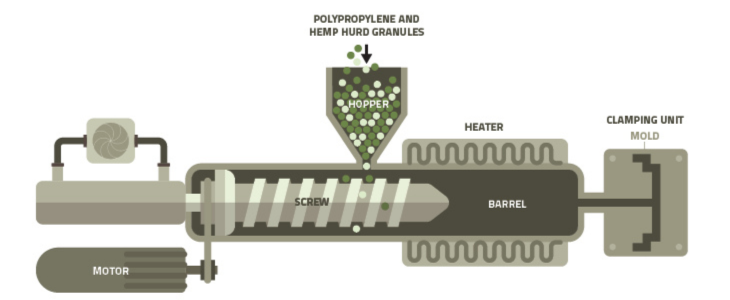

Injection molding 101

Injection molding is a widely used manufacturing technique for producing plastic parts. It was identified as the best method for fabricating Earthware food containers because of its precision, repeatability and suitability for complex part designs.

Step 1

After being blended by an extruder, the Earthware project's mix of polypropylene and hemp hurd pellets is fed through a hopper into the injection unit, where it is melted and stirred by a heated screw.

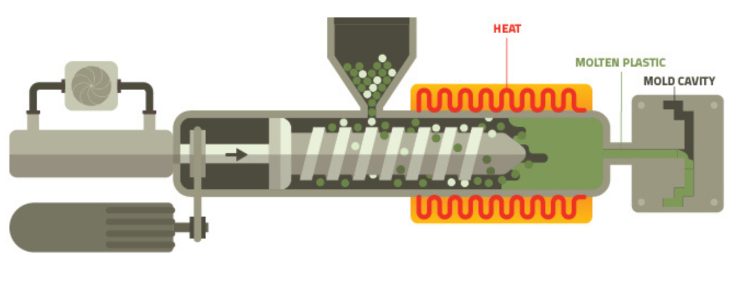

Step 2

Step 3

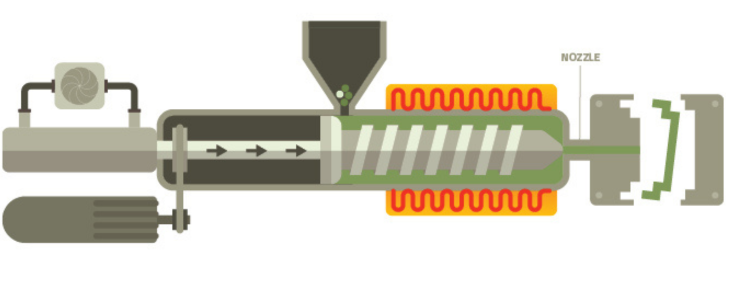

When the barrel is full, the injection begins. The machine speeds up the screw and supplies enough pressure to inject the remaining plastic through the nozzle and into the mold.

Inside the clamping unit, channels filled with running water cool the mold. Once sufficiently cooled, the clamp opens. The cup falls out of its mold, the screw moves back, the hopper releases more granules into the barrel, and the whole process — lasting about 20 seconds — starts again.

A force to be reckoned with when reducing single-use waste

Earthware's quest to remove 1 million takeout containers from Alberta landfills by 2025, got a generous boost from Canadian Food Innovation Network (CFIN) in 2023. They funded a project through Southern Alberta Institute of Technology (SAIT) to create the ultimate reusable takeout container.

Earthware return-for-refund and reuse containers already out perform single-use containers of any kind when it comes to reducing the impact on our planet. With projects like these, we can figure out how to exponentially increase use and hopefully get to a place where single-use containers are a thing of the past.

Like what you are reading?

Find more stories from past, present and upcoming issues of LINK magazine!

Oki, Âba wathtech, Danit'ada, Tawnshi, Hello.

SAIT is located on the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of Treaty 7 which includes the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina and the Îyârhe Nakoda of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney.

We are situated in an area the Blackfoot tribes traditionally called Moh’kinsstis, where the Bow River meets the Elbow River. We now call it the city of Calgary, which is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta.