Today’s expanding aviation industry is connecting more people through travel, sparking economic growth worldwide, and incorporating new technologies like artificial intelligence and alternative fuels. And, with Alberta emerging as a global aviation hub, SAIT’s Art Smith Aero Centre for Training and Technology is celebrating 20 years at the forefront of aviation training.

Fueling economic growth

With Alberta's history as an agricultural and oil and gas hub, it may seem like our province’s wealth comes only out of the ground. But even greater economic prosperity might soon be found in its skies. Alberta’s aerospace and defence industry is growing, attracting more national and international aviation companies to the province and generating upwards of $3.25 billion in provincial GDP.

In addition to two of Canada’s busiest airports (Edmonton and Calgary), this province is home to the Canadian Armed Forces’ largest research centre. Calgary is also the first North American city to allow mass testing of commercial drones, and SAIT’s Centre for Innovation and Research in Unmanned Systems (CIRUS) is on the leading edge of the growing RPAS industry (remotely piloted aircraft systems). Last year, Canadian aircraft manufacturer De Havilland announced it is building a new facility in Wheatland County, providing an anticipated 1,500 jobs for Albertans.

A major driver in this influx of aerospace business is the availability of skilled labour. “Companies are looking to hire individuals who have post-secondary education,” says Lynda Holden (AMT ’93), Interim Dean of the School of Transportation and the School of Manufacturing and Automation. “We offer the only Transport Canada-approved aerospace training in Alberta, so SAIT is well-positioned to meet those workforce needs.”

As aviation technology advances, the types of roles that companies need to fill will diversify. “Over the next 10 years, we’ll need pilots and aircraft maintainers, but we’ll also need an expanded support system. That includes aircraft repair and overhaul plus cybersecurity, data and analytics, supply chain management and accounting,” Holden says. “SAIT really offers a wide breadth of applied learning that employers are looking for.”

Holden sees blue skies ahead for the aerospace industry. “There’s enormous potential for growth,” she says. “I anticipate aerospace and defence to play an even larger role in Alberta’s economy moving forward because we can provide skilled workers.” — KP

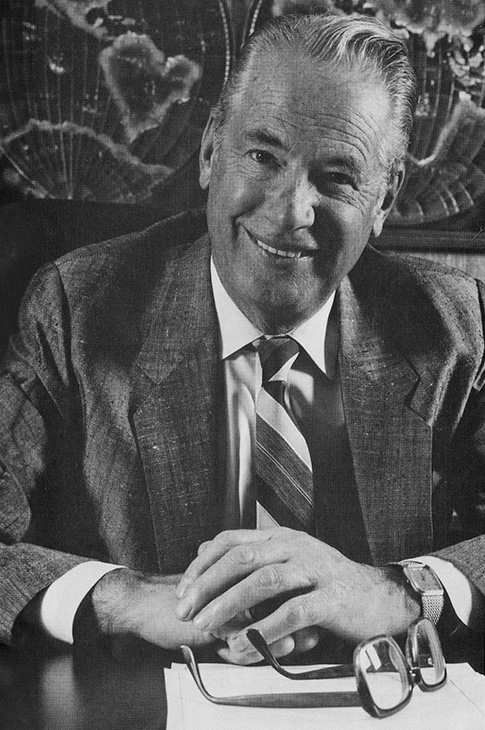

Who was Art Smith?

Deep in SAIT’s donor files is a report from a staff member who, in the mid-2000s, accompanied Art Smith to an important meeting with an airline vice president at the Art Smith Aero Centre.

“It was a challenge getting from the front door to the elevator,” wrote the staffer, “not because of any frailty on Mr. Smith’s part, but because the Aero Centre was buzzing with students and Mr. Smith stopped to say hello to at least four of them.”

The same thing happened when they exited the elevator: “More students, a beaming smile on Mr. Smith’s face, purposeful questions about a particular student’s course selection.”

That sense of purpose drove Smith throughout his life. He started work at the Turner Valley oilfields at age 16. He was a Royal Air Force bomber command squadron leader during the Second World War, received the Distinguished Flying Cross, and became a test pilot for the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was president of two aircraft firms and a member of the Air Crew Association.

In 5,500 hours of flying time, Smith recalled, “Every time my wheels touched the ground I would say, ‘Thank God for the maintenance crews.’ I owe it to them that I’m here.”

After the war, he was a publisher, business executive and entrepreneur. He served as a city councillor, an Alberta MLA, a member of Parliament, and a delegate to the United Nations. He founded the Calgary Homeless Foundation and was active with multiple organizations and charities. — NC

In 1988, Smith was invested as a Member of the Order of Canada and was elevated to Officer level in 2003 for his continued service to Canada. He also received the Alberta Order of Excellence and honorary degrees from SAIT and the University of Calgary. A beloved family man and a leader in the community, he led the charge to secure funding for the Aero Centre that today bears his name.

Photo by Wes Raymond

Fixing on the fly

For 2013 aircraft maintenance engineer graduate Jen Erickson (pictured left, photo by David Landy), repairing airplanes on the Antarctic ice sheet is just another day on the job.

Erickson works for Rocky Mountain Aircraft, where she and the maintenance team focus on heavy overhauls. But every year, she also travels south to work on planes with the British Antarctic Survey program.

Working in one of the world's most remote areas wasn’t something Erickson had considered before joining the company. Instead, it was the opportunity to stretch her skill set that attracted her to the job. “I knew I wanted to be more well-rounded in my scope of expertise,” she says.

From October to March, Erickson is part of the crew responsible for line maintenance on the survey program’s four Twin Otter aircraft — two for scientific fieldwork and two for cargo transport. Operations rely heavily on these aircraft, so they’re constantly flying. They need regular checks, fast repairs and ongoing maintenance approximately every 100 hours.

“You don’t know what’s going to happen each day,” Erickson says. “You get to be a bit of your own manager and do what needs to be done to get the airplane serviced or fixed as quickly and safely as possible.”

Erickson loves the challenge of fixing aircraft — quite literally — on the fly. “The best part of the job is also the hardest part of the job. In Antarctica, things are unpredictable. Doing repairs out in the field, you might not have the right part or the right resources to get the job done,” she says. “But it’s really satisfying when you push yourself to your limits and you fix it; you’ve accomplished something. You just need to be a little bit creative.” — KP

Beyond the cabin

“No airplane would fly without skilled maintenance engineers and technicians, but travellers rarely think about us,” says Stephanie Hogewoning (AXT ’06), Academic Chair, Aviation.

“The reason your plane is sitting at the gate, all ready to go, is because of maintenance that’s happened in some hangar, far from the terminal, at 3 a.m.”

Every day, YYC Calgary International Airport hosts more than 250 passenger flights. Each requires a huge investment of human capital.

“If it's an overseas flight, you're looking at four pilots, depending on the length of the flight,” Hogewoning says. “Then there’s up to 12 cabin crew just to operate the airplane.”

After landing, ground crews refuel the plane, handle baggage, and help tow the aircraft to where routine maintenance is performed by two to three technicians. If major repairs are required, as many as 10 people across multiple trades and disciplines will be involved.

“Very conservatively, it can take 30 skilled people to get a flight to its destination,” Hogewoning says. — NC

Avionics agility

It takes much more than wings or propellers to keep an aircraft flying safely. All pilots rely on a network of electronics — including communication, navigation and data systems — to take off, find their way to their destination, and land. In today’s aircraft, hundreds of electrical components (known as avionics) must be installed, maintained and upgraded to meet rigorous industry standards and technological advancements.

That’s where avionics technicians like Brett Dembicki (AXT ’24, ENT ’18) come in. “We’re responsible for all the transmission systems, from navigation and radio communications to the terrain avoidance and warning systems,” Dembicki explains. “We need to ensure all these systems interconnect with the autopilot system to provide a safe flight.”

That’s where avionics technicians like Brett Dembicki (AXT ’24, ENT ’18) come in. “We’re responsible for all the transmission systems, from navigation and radio communications to the terrain avoidance and warning systems,” Dembicki explains. “We need to ensure all these systems interconnect with the autopilot system to provide a safe flight.”

Being an avionics technician requires constant on-the-job learning, a flexible skill set and a problem-solving approach. “In the Avionics Technology program, they told us, ‘You’ll be working on stuff that’s 50 years old all the way up to modern technology.’ They really prepared us to be able to troubleshoot anything,” he says.

Today, Dembicki works in the Avionics Division at Avmax — one of Canada’s largest avionics support facilities — where he recently helped install new SKYTRAC satellite communications systems in Cessna airplanes used by Alberta Health Services to transport patients between hospitals. This cutting-edge system allows direct radio communication between the hospital and the plane while in flight. He also works on planes with older technologies such as analogue altitude indicators, which involve gyros, gears and bearings that allow a pilot to orient their plane on the horizon.

Having experience with decades of technology provides a backbone of knowledge Dembicki can draw on when working with new systems. “Every system is like a fancy LEGO set with very specific requirements,” he says. “When I encounter something new, I know that I’ve seen something similar before, and I can always use that as a starting point.” — KP

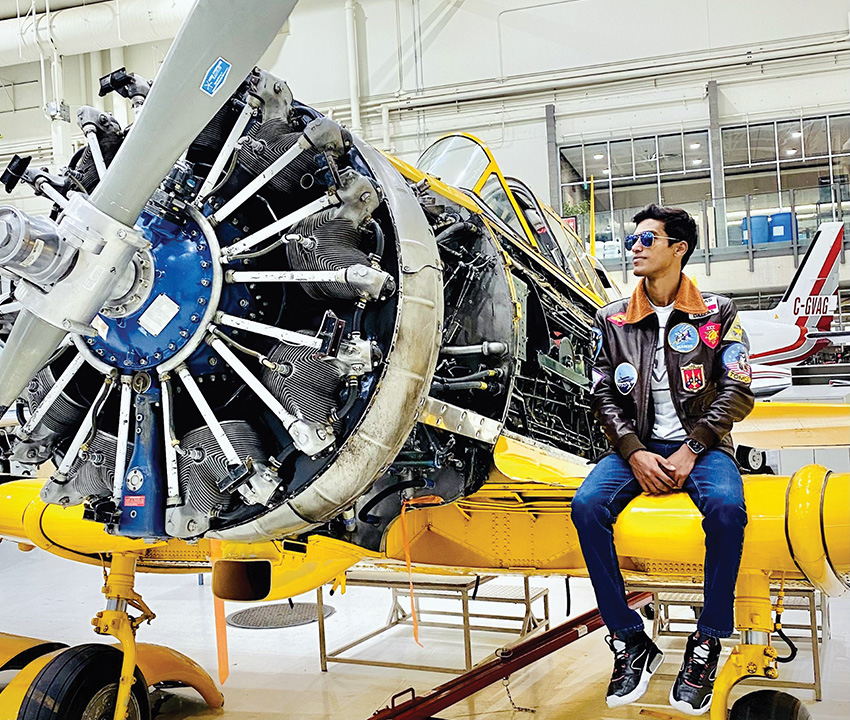

Creativity and (air)craft

Aircraft structures technician Benjamin Matlo (ACST ’23) has always had a knack for putting things together. An avid model train builder since childhood, Matlo’s original career track took him into the (life-sized) rail industry. In 2022, Matlo pivoted into aerospace, where he saw greater potential to expand his skill set and pursue a broader range of job opportunities.

Aircraft structures technician Benjamin Matlo (ACST ’23) has always had a knack for putting things together. An avid model train builder since childhood, Matlo’s original career track took him into the (life-sized) rail industry. In 2022, Matlo pivoted into aerospace, where he saw greater potential to expand his skill set and pursue a broader range of job opportunities.

After graduating from SAIT last year, he snagged an apprenticeship at Chinook Aviation Inc., where he works on helicopters. As a structures technician, his job focuses on repairs and maintenance to the body of the aircraft, essentially “anything that holds the machine together,” he says. “We work on sheet metal and composite parts like fibreglass, carbon fibre or kevlar. I’ve also had the opportunity to learn how to paint helicopters.”

Working in a small shop like Chinook Aviation has allowed Matlo to try out a variety of jobs — an experience that gives him the chance to be highly creative. “Using your imagination is a huge part of making repairs,” he says. “Whatever you’re fixing usually has some set parameters, and sometimes, it can be pretty difficult to figure out how to make things work and make it look like the repaired area has always been there.”

Matlo credits his SAIT instructors for providing the space he needed to develop the creative and critical thinking skills he uses in his job every day. “My composite repair instructors were more than happy to help me experiment with different things,” he recalls. “They let me come up with solutions that were better than what was originally part of the assignment description.”

Matlo sees his current job as a gateway for both personal and career exploration. “I love learning new things,” he says. “The way I see it, the better I get at this, the more things I can do.” — KP

The future of flight

Looking ahead, Lynda Holden has an ambitious vision for the Art Smith Aero Centre for Training and Technology. “Over the next 20 years, I see the Aero Centre growing to twice its current size,” she says.

Looking ahead, Lynda Holden has an ambitious vision for the Art Smith Aero Centre for Training and Technology. “Over the next 20 years, I see the Aero Centre growing to twice its current size,” she says.

It’s already one of the largest aviation programs in Western Canada, but the demand for skilled professionals to maintain commercial, private and military aircraft is only increasing. And, Holden says, the massive technological advancements rapidly transforming aviation are “posing new opportunities for us to change how we teach and what we teach.”

For example, the recent addition of SAIT’s Professional Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems diploma program — the first of its kind in Canada — positions the Aero Centre as a leader in advanced air mobility, unmanned flight and drones.

“As a pilot, Art Smith truly valued the importance of aircraft maintainers,” Holden says. His inspirational achievements continue to inspire and elevate the training centre named in his honour, preparing new generations for the vital, behind-the-scenes roles that make the future of flight possible." — KP

Oki, Âba wathtech, Danit'ada, Tawnshi, Hello.

SAIT is located on the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of Treaty 7 which includes the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina and the Îyârhe Nakoda of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney.

We are situated in an area the Blackfoot tribes traditionally called Moh’kinsstis, where the Bow River meets the Elbow River. We now call it the city of Calgary, which is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta.