"I'll ask the universe for guidance"

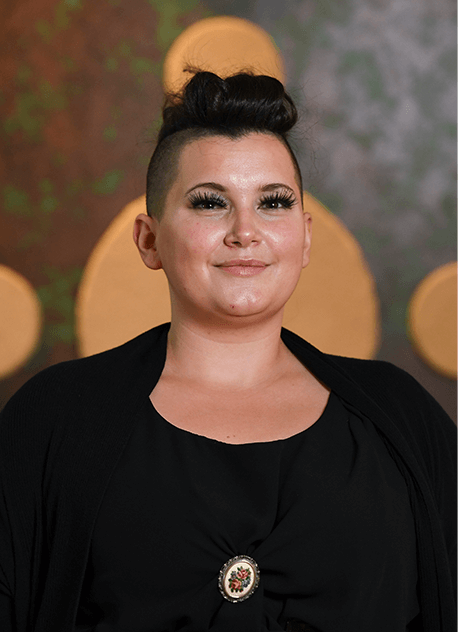

When Angelina Orlando looked at SAIT as an education option five years ago, she realized she didn’t qualify for any of the programs offered.

She was a high-school dropout, working a minimum wage job that was physically taxing. I said to myself, ‘There has to be another way,” Orlando remembers.

Shortly afterwards, she received a phone call from her sister saying there was an upgrading program for Indigenous students at SAIT. I’m a very spiritual person,” Orlando says. I’ll ask the universe for some guidance, and I believe that’s how I ended up at SAIT.”

She enrolled in the Academic Upgrading Indigenous Program (AUIP), a 12-month series of academic courses, cultural activities, and post-secondary readiness sessions. Created by SAIT’s Chinook Lodge Resource Centre, the AUIP begins for students at the Grade 9 level and eases their transition into further study at SAIT or other post-secondary institutions. It ends with the completion of Grade 11 and 12 courses.

Angelina Orlando AUIP graduate and current SAIT Business Administration student.

It’s just one way the Lodge is helping meet the four strategic priorities outlined in SAIT’s Indigenous Learner Success Strategy: access, success, awareness and community engagement.

Orlando completed the AUIP earlier this year with a GPA of 3.8, which astonished her as she’d never received an A in her academic career before. She immediately enrolled in SAIT’s Business Administration diploma program and plans to continue her studies with the Bachelor of Business Administration program after that.

When COVID-19 restrictions permit, Orlando spends a lot of time at the Lodge where she goes to pray, hang out with friends and practice ceremonies. “It’s like home,” she says. “We’ve set up a tipi, and there’s even beading and jig classes.”

Playing a larger role

Located in Room NN108 of the Senator Burns Building (and opposite Tim Hortons), the Lodge was established in 2001 to increase retention rates of Indigenous students and support them in their program of study.

Today, as it celebrates its 20th anniversary, the Lodge continues to function in much the same way, but it also provides access to advisors and career counsellors, helps students develop successful learning strategies, and offers events that celebrate Indigenous heritage. Elders are available for cultural and spiritual guidance, and the Lodge hosts networking events where students can meet prospective employers. The space is an inclusive environment that’s open to all members of the SAIT community, including alumni.

“The Chinook Lodge has taken on a greater role in addition to retention and recruitment,” says Larry Gauthier, Chinook Lodge Coordinator. “And that’s providing cultural awareness within the institution for faculty, staff and students — not just the Aboriginal students, but the whole campus community.”

Chinook Lodge Coordinator Larry Gauthier

Gauthier mentions that he avoids the use of the term “Indigenous” because he and other Elders believe there are no rights associated with that word. “Our rights as Indian, Métis and Inuit people are entrenched in Canada’s Constitution as Aboriginal Peoples,” he says.

He describes the Lodge as an ethical space where non-Aboriginal students can learn about Aboriginal culture, history, epistemology (the study of human knowledge), worldviews, values and belief systems.

This has become increasingly important since 2015 when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) made 94 Calls to Action to advance reconciliation efforts between Canadians and Indigenous Peoples. Several of those calls outline significant roles for post-secondary institutions, including furthering reconciliation by integrating Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into the classroom.

In particular, Gauthier wants to see the Lodge as the epicenter of Indigenization at SAIT. He believes a new leadership position needs to be created within the Institute so there is an Aboriginal, senior-level person responsible for coordinating Indigenous initiatives across SAIT. That person would also build connections between Indigenous communities and the Institute, and advocate for the implementation of the TRC Calls to Action.

“We do a lot of cultural teachings within the Lodge, and we bring in Elders and Knowledge Keepers,” says Gauthier. “But SAIT needs to have a person who sits on its decision-making bodies, where they can effect and introduce changes like including Aboriginal curriculum in all SAIT programs.”

Although the Lodge has great allies and supporters within the Institute, there’s no formal, coordinated effort towards incorporating the TRC Calls to Action, Gauthier says.

“With a senior-level person who could sit down as an equal to a dean, we could say, for example, ‘Here’s Call to Action 86, here’s some suggestions on incorporating Aboriginal content into your academic program, and we’re happy to help develop and work on this,’” Gauthier says.

In the meantime, Gauthier has brought in Elder Kerrie Moore to provide spiritual balance as part of the Lodge’s support services. She believes access and retention are still barriers for Indigenous students attending post-secondary. “When you look at the research about retention rates of Indigenous people in education, it comes back to the same thing, which is hearing those students say, ‘I felt uncomfortable in an environment that I didn’t understand, that didn’t understand me, and that made me feel like I wasn’t good enough — so I left’,” says Elder Moore, an educator and psychotherapist who specializes in intergenerational trauma and grief.

She counsels students, provides traditional teachings, and offers her grandmother tea ceremony to students and staff. Elder Moore points out that residential schools created a fear of education, and it continues to be a psychological block for many Indigenous students today.

“We have to recognize that the fear we carry about education didn’t start with us,” she says. “It started with those ancestors who were children, yet we carry the shame that is connected to everything that happened to our ancestors.”

Elder Moore explains that a sense of familiarity is especially important to Indigenous students because trauma is based on what we hear, smell, see, taste and touch. Our senses create fear for us, she says. Familiarity is what creates safety.

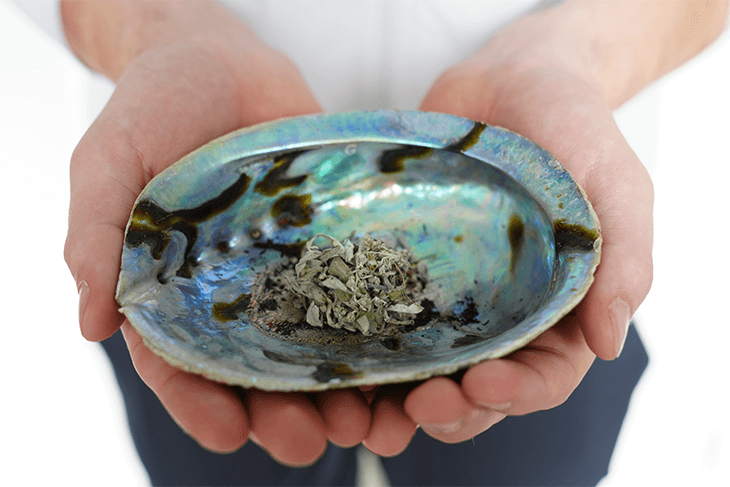

When Gauthier remodelled the Lodge recently, he created familiarity for Indigenous students. “When you walk in the door, your brain picks up sensory feelings, thoughts and smells,” says Elder Moore. “That’s how your brain determines whether you’re safe or not.”

Gauthier created a circular ceremonial room for prayer; he hung a moose hide on the wall and traditional prints on the ceiling. The smell of sage is prominent throughout. “Students feel safe in the Chinook Lodge,” says Elder Moore.

When she started working with the Lodge in 2018, Elder Moore realized that students also wanted to continue their own cultural practices, but were desperate to balance those practices within mainstream education. “My role is to keep students connected to spirit,” she says. “Which is where we hold our values of love, kindness, respect, honesty, compassion and accountability. We carry that in our spirit, which isn’t a religion; it’s a place in our body.”

As Elder Moore guides students through ceremony, they gain the ability to see that the day-to-day processes they will experience in a post-secondary environment are nothing to fear.

She creates a relationship with the students and provides familiar practices to help them feel invulnerable. “We have lunches together with soup and bannock; we laugh and chat together,” she says. When you walk into a space, you want to see yourself. When you see familiar protocols, the fear dissipates.”

To be most effective, support for Indigenous students needs to be immediate and readily available. If they can’t find support right away, Indigenous students often become overwhelmed and leave. What follows are feelings of shame and guilt, Elder Moore explains.

“Part of creating an ethical space is to make sure the supports are right there so students don’t have to search for them,” she says. At Chinook Lodge, Indigenous learners can access everything from advising and counselling, to assistance with financial aid and housing, to computers and study space.

“In order to change your brain, you have to be successful,” she says.

Sarah Dahlberg (AUIP '21)

Set yourself up for success

To be most effective, support for Indigenous students needs to be immediate and readily available. If they can’t find support right away, Indigenous students often become overwhelmed and leave. What follows are feelings of shame and guilt, Elder Moore explains.

“Part of creating an ethical space is to make sure the supports are right there so students don’t have to search for them,” she says. At Chinook Lodge, Indigenous learners can access everything from advising and counselling to assistance with financial aid and housing to computers and study space.

“In order to change your brain, you have to be successful,” she says.

Now she is poised to become a mentor herself, through a new grant the Lodge has received from the Calgary Foundation that enables technologically proficient Indigenous students to mentor new Indigenous students online.

Dahlberg is incredibly proud of seeing the opportunities offered through the Lodge and applying herself to making the most of them. Chinook Lodge staff helped her gain confidence as she prepared for her first term — and she’s taken those practices into her daily routine.

I study so much in my life right now,” she says. I’m surpassing my goals and it’s a great feeling. It makes me really proud, not only to be a student at SAIT, but to be an Indigenous student and achieving these goals.”

A space to be seen and heard

Kassie Haley (AIM ’19) agrees it’s important to hold a safe space for Indigenous students — especially students coming from on-reserve. “If they’re not an urban Indigenous person, they might feel a loss of connection because they can’t participate in ceremony, or can’t relate to certain people at the school, says Haley. “Chinook Lodge creates a space for Indigenous students to feel seen and heard.”

Haley currently works in administration and human resources at Suncor. As an AIM student, she did her practicum there, which helped her create connections and opportunities that she benefits from today. “It was a really good experience and helped me find my place in the workforce, she says.

Haley’s educational journey also included serving as Co-chief and Financial Executive of the SAITSA Indigenous Students’ Alliance, working to facilitate events and ceremonies for Indigenous peers.

Kassie Haley (AIM '19)

“We did things like sweat lodges, movie days and lunches, says Haley. “I spent a lot of my lunchtime at the Lodge as well as time in between classes. I’d get my work done or meet friends. I spent a lot of time there, and I enjoyed it.”

For Haley and countless others, the Chinook Lodge Resource Centre is a safe space to be Indigenous. It offers a respite from the delicate balancing act Aboriginal students experience as they walk in two worlds — traditional and academic. It’s a space where an Indigenous student can step through the door and not be a minority in their own territory.

“You must have a separate ethical space that is treated as ceremonial — with kindness, respect and protocol, Elder Moore says. “As a student, you can’t step into anything unless you have cultural support to guide you in ceremony, and to provide the ability to recognize that, ‘I don’t need to be afraid. With this support, I can do anything.'

"...a special place in my heart"

From reconnecting with culture to making lifelong friends, the Chinook Lodge Resource Centre will "forever hold a special place" in Stephanie Joe's heart. As she reflects on her time at SAIT and the experiences she gained from Chinook Lodge, Joe wishes future students to find belonging like she did.

This story was originally written for the print version of the Fall 2021 issue of LINK.

NOTE: Masks were removed indoors for photos only.

Building a better future

Thanks to a recent commitment from our donor family, support for Indigenous education is set far into the future with the Aboriginal Futures Endowment Fund.

Oki, Âba wathtech, Danit'ada, Tawnshi, Hello.

SAIT is located on the traditional territories of the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) and the people of Treaty 7 which includes the Siksika, the Piikani, the Kainai, the Tsuut’ina and the Îyârhe Nakoda of Bearspaw, Chiniki and Goodstoney.

We are situated in an area the Blackfoot tribes traditionally called Moh’kinsstis, where the Bow River meets the Elbow River. We now call it the city of Calgary, which is also home to the Métis Nation of Alberta.